Auctions in Germany – how are they working? in Japanese

and lead author of GermanEnergyTransition.de.

Around the world, auctions have been touted as a way of bringing down the cost of renewable electricity. In his brief overview, Craig Morris points out why that is – and what else we lose in the process.

Partly at the behest of the European Commission, Germany is transitioning from feed-in tariffs to auctions, a process that is to be finished by 2017. As of November, only two pilot auctions have been conducted for ground-mounted PV. The results have been mixed too negative.

First, the price – the first round produced a price of 8.93 to 9.17 cents per kilowatt-hour. The second round produced a much lower price of 8.49 cents, but winning bidders have 24 months to complete their projects. Two years from now, feed-in tariffs would reach 8.43.

But didn’t auctions recently lead to record low solar prices of around six cents in Dubai? Yes, but then the United Arab Emirates has twice as much sunlight as Germany. The same panel therefore produces roughly twice as much electricity. The arrays built in Dubai would produce solar power for 12 cents in Germany. Apparently, auctions have yet to produce the low prices already offered by German feed-in tariffs when adjusted for Germany’s for solar conditions.

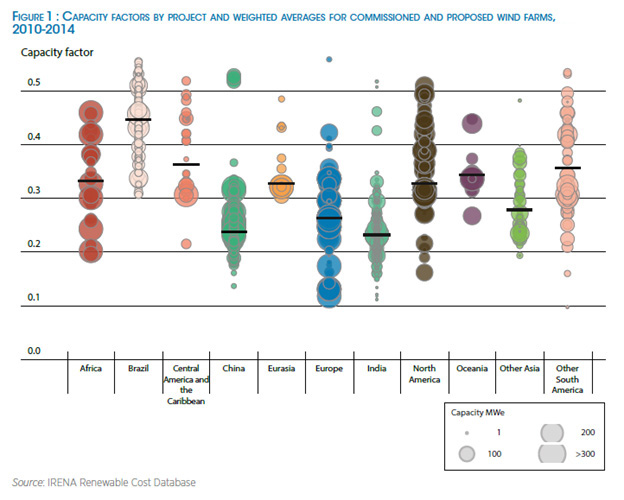

Here, we need to talk about capacity factors (CF). The chart below from IRENA shows the average CF of wind farms around the world by region. The CF is the percentage of power produced relative to the maximum amount possible; for wind turbines, CF indirectly reflects wind conditions. The size of the bubbles indicates the volume of wind farms built at that CF. Worldwide, Europe (particularly Germany) has built wind turbines in areas with quite poor wind conditions. In contrast, Brazil has built wind farms in areas with the best wind conditions on average and therefore has the highest CF of all. Now guess which country was praised in 2013 for the success of its auctions in bringing down the price of wind power? (Hint: it’s the one with the best wind conditions.)

Proponents of auctions say that the policy brings down prices because bidders compete with each other. In reality, another type of competition is also going on. Auctions make sites with poor wind/solar resources compete with the best sites. The result is a lot of wind turbines in the windiest areas and solar arrays in the desert.

Other results include greater costs for grid extensions, (potentially) more public resistance to gigantic wind farms altering the appearance of attractive coastlines, and market concentration – that’s right, the policy that allegedly increases “competition” actually reduces the number of market winners. Smaller firms that lose in one auction may not bother bidding in the next (participating in auctions costs money). The result could eventually be higher prices once the big players have crowded out small competitors. And indeed, the results of more recent wind power auctions in Brazil show that the number of winners is down and prices are up.

The German government launched its PV auctions explicitly with the aim of testing the policy to see whether “the energy transition will be less expensive this way,” as the coalition agreement of November 2013 states. Now that everyone can see that prices are basically the same, the government meekly speaks of “keeping policy cost down” (official paper on auctions from July 2015) without any claim that auctions produce lower prices than feed-in tariffs.

What’s worse, German PV auctions have already had a devastating effect on the number of market winners. The first round attracted 170 bids for 25 contracts, meaning that there were 145 losers – 80 percent of participants. In the second round, there were 103 losers and 33 winners in the second round – 75 percent losers. No citizen energy cooperative won in either round.

So why is the German government sticking to the transition to auctions? One reason certainly is that the European Commission prefers them to feed-in tariffs. But the real reason is probably different: feed-in tariffs failures look like a governmental failure, but when auctions fail, it looks like a market failure. If an auction does not produce the low price expected, well, politicians didn’t set the price – the market did. If a company that wins a bid fails to fulfill the contract, that company fails, not politicians. Such a situation is inherently attractive to policymakers facing elections.

To be fair, auctions are a common and useful way for governments to purchase large infrastructure that cannot be bought off the shelf. What’s the price of that new bridge we want? We’ll have to ask a few companies – online shops will be of little help.

But renewable energy projects are different. They can be small. Some would argue they should be small – and the volume should come from large numbers of them. The European Commission proposes that small projects below six megawatts be allowed to go forward with feed-in tariffs without having to take part in auctions. Governments that prefer auctions for large wind farms and solar arrays should consider leaving feed-in tariffs in place for smaller projects driven by municipalities, citizen cooperatives, and small businesses. Such projects will strengthen SMEs and rejuvenate rural communities. It will also produce more winners, thereby giving more people ownership of governmental policy.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of German Energy Transition. He directs Petite Planète and writes every workday for Renewables International. He is grateful to Patrick Matschoss of the IASS for input into the German government’s changing justification for the switch to auctions.