The fiscal 2018 Procurement Price Calculation Committee spent considerable time discussing the sustainability of bioenergy fuels. As an expert in the field, the author was in attendance at the 43rd committee meeting held on December 20 and expressed his opinions on the matteri.

Thereafter, at the final meeting of the committee on January 9, 2019, a general direction was agreed upon, but it was determined that a separate working group would be established to consider the details in their specialized and technical aspects, and these forthcoming discussions will be very important.

This column comments on the key points of this fiscal year’s discussions and organizes issues that should be discussed by the working group.

How Should New Fuels Be Handled?

In fiscal 2018, requests for new FiT approval were submitted by two industry groups for solid and liquid fuels.iiThe first point of discussion was the perspectives from which to classify the diverse range of fuels and judge their suitability for FiT certification.

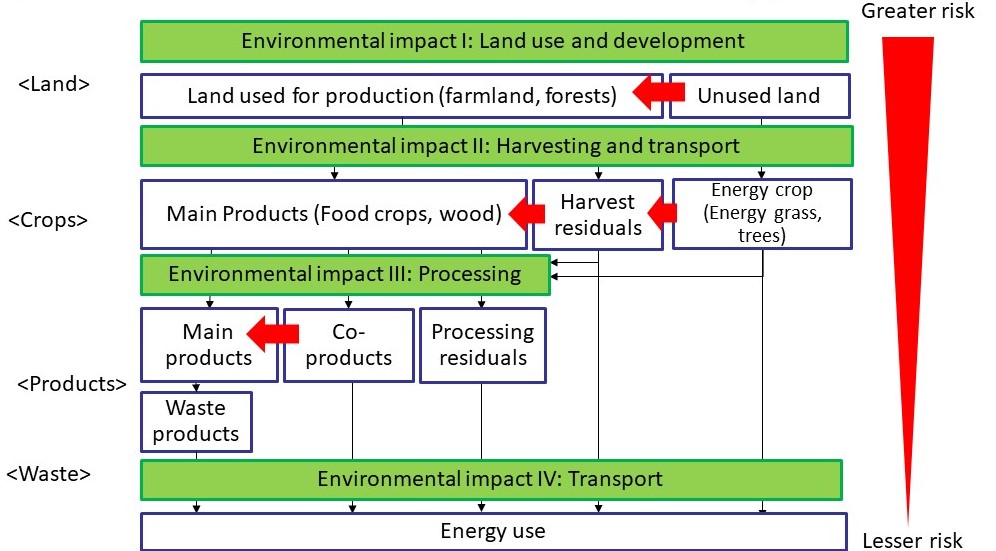

In terms of classification, what is important, first of all, is the stage at which the fuel is produced, from production to disposal (Figure). For example, if the fuel comes from a waste stream, the environment impact and the risks associated with use of the energy are low. On the other hand, if a crop is grown expressly for use as a new biofuel, unless the land is unused such as abandoned farmland, production of the fuel could lead to deforestation or conversion of existing farmland. Moreover, as is the case with vegetable oil, if there is the possibility of competition with a food product, the matter needs to be handled with special care.

Also, the fuels for which requests were made this fiscal year call for caution in light of the fact that they include fuels like empty fruit bunches (EFB)iii from oil palm for which the environmental impact needs to be verified, including at the processing stage. EFB needs to be cleaned and modified for minerals such as soidum, potassium and cholorine, and requires palletization. This process gives off highly concentrated organic wastewater, so the potential for environmental pollution has been pointed outiv. For this reason, assessments need to be appropriately conducted that include this type of environmental impact at the processing stage.

Figure: Stages of bioenergy fuel from production and disposal, and environmental impacts

Source: Created by Renewable Energy Institute with reference to categories in the EU Renewable Energy Directive

How Should Fuels Be Appropriately Certified for Sustainability?

Sustainability standards are used as a tool to certify diverse fuels. Which certification schemes to utilize, therefore, will be an important point of discussion for the working group.

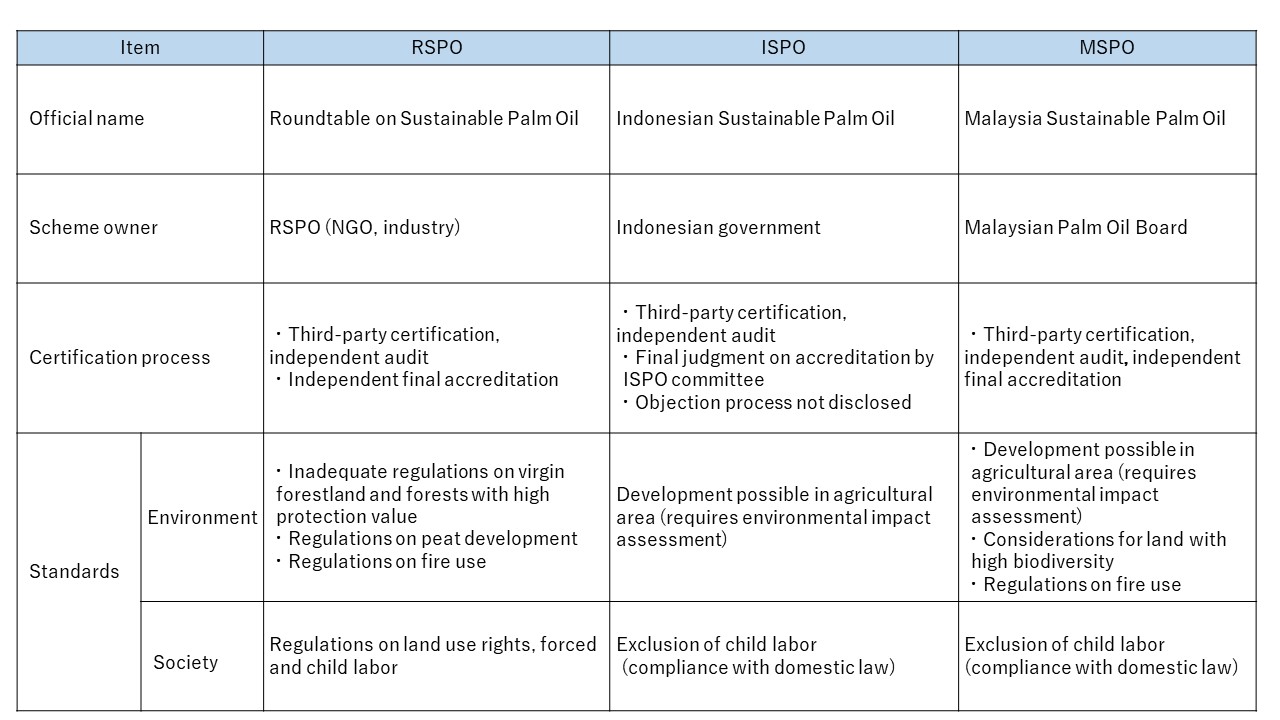

In fact, this fiscal year, the discussions regarding which certification scheme is appropriate has already surfaced with respect to palm oil. Palm oil possesses various risks related to sustainability; the potential is even there for it to have a greater environmental impact than fossil fuels.v In Japan, until fiscal 2017, in light of this risk, the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), which is highly trusted worldwide, was indicated as the certification scheme that could be utilized, and sustainability had to be secured at a high level. However, in fiscal 2018, on the grounds of the high barrier to RSPO certification, an industry group submitted a request to have Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) and Malaysia Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) recognized as equivalent certification schemes.

However, as has been made clear by existing researchvi, it would be difficult to recognize ISPO and MSPO as equivalent to RSPO (Table). Third-party certification, as originally conceived, utilizes market principles: consumers demand a level higher than legal compliance and suppliers reaching that level receive a premium. In other words, a majority of private-sector certification schemes like RSPO require a level that exceeds the law applied in the producer country. However, ISPO and MSPO are schemes owned by the Indonesian and Malaysian governments respectively, and a majority of the standards do not go beyond compliance with domestic law.

The transparency of the management of the scheme is also important. For example, to ensure stringent certification, it is commonly the case that the scheme owner does not participate in the final decision on certification. However, with ISPO, the final decision on certification is made by the Indonesian government, and transparency is an issue.

It is true, however, that these certification schemes endeavor to make improvements, and the possibility of being judged as equivalent to RSPO in the future cannot be denied. In addition, fuels like palm kernel shells (PKS)vii that are already FiT certified will also be subject to sustainability confirmation going forward. Certification schemes are ultimately only a tool for verification, and comprehensive discussions are needed to identify items subject to verification based on the risks of each fuel.

Source: Created based on “Study on the environmental impact of palm oil consumption and on palm oil consumption and on existing sustainability standards,” DG Environment (2017)

How Should the Working Group Be Structured?

Given the comments of multiple members of the Procurement Price Calculation Committee, working group discussions are expected to be conducted on an expedited basis. However, it is important that appropriate members are selected to exclude the influence of specific companies and industries; discussions will need to be conducted based on objective data.In addition, with regard to initiatives to secure the sustainability of biofuels, Europe has taken the lead, and it will be necessary to work for international coordination while leveraging Europe’s expertise. IEA Bioenergy, the institution demonstrating international leadership in this area, held an international workshop in Tokyo in September 2018, and there are expectations for Japan’s active participation and increased dialogue with Asian countries that produce and export fuelsviii.

Finally, one of the important roles the working group should fill is monitoring the fuels used by power plants. First, to mitigate the risk of admixtures of non-certified fuels, it is necessary for the supply chain, including power plants, to acquire certification. Next, third-party certification schemes, like RSPO, conduct annual audits and renewal audits every three to five years, so certification acquisition and maintenance also need to be confirmed. Along with checking individual power plants, the macro level impact of the FiT scheme on fuel usage needs to be monitored from environmental and social perspectives and scheme adjustments and improvements made as necessary.

- i “For Securing the Sustainability of Bioenergy Fuels” (43rd Meeting of Procurement Price Calculation Committee; held December 20, 2018)

- ii 39th Meeting of Procurement Price Calculation Committee (held October 24, 2018); Biomass Power Association’s “Biomass Power Project: Current Situation and Future Prospects,” and Biomass Power Association’s “Issues and Prospects of Biomass Liquid Fuel Power Projects (Palm Oil Power Generation)”

- iii Empty fruit bunches from palm oil production

- iv “Key Points in Securing the Sustainability of Power Generation Biomass from Crop Harvesting,” Satomi Funahashi, Fuji Keizai (179th Workshop of Biomass Industrial Society Network, November 13, 2018)

- v “Great Risks Involved in Palm Oil Power Generation: Sustainability Standards Are Urgently Needed,” Takanobu Aikawa (Renewables Update, September 4, 2017)

- vi Major studies commissioned by the European Commission: DG Environment (2017) “Study on the environmental impact of palm oil consumption and on existing sustainability standards.”

- vii Palm shells remained after palm oil production

- viii “IEA Bioenergy Workshop Report: Sustainable Bioenergy Use in Asia,” Takanobu Aikawa (Renewables Update, October 12, 2018)