|

Australia is as big as a continent and rich in multiple energy resources (fossil fuels, uranium, and renewable energy). The country is well-known as a global leader for coal and liquefied natural gas exports. It has, however, not yet established itself as a major renewable energy powerhouse despite its evident potential. Massive amounts of electricity could be generated from cheap wind and solar power. This electricity combined with the latest technologies, including batteries, virtual power plant networks, high voltage direct current undersea cables, and electrolysers, could not only help meeting Australia’s energy needs, but also significantly contribute to decarbonization efforts in other countries, especially in Asia, thanks to green electricity & hydrogen exports. This ambition is already shared by forward-thinking Australian States and Territories which are now all aiming for carbon neutrality by around mid-century. Lagging behind for the moment, the Federal Government, together with industrial vested interests in fossil fuels, slows down inevitable progress. Japan and Australia are each other’s main trade partner for coal and liquefied natural gas, and Japan is now moving towards carbon neutrality by 2050. Therefore, with these existing strong interdependencies and new commonly shared climate & energy ambitions, there is a solid and promising ground to rethink beneficial collaborations between the two countries. |

|---|

Story

When it comes to climate & energy, Australia offers the extraordinary contrast of a quite divided country at the national and sub-national levels. While the Australian Federal Government is infamously recognized as a laggard in this field, States and Territoriesa demonstrate a certain leadership, that is sometimes particularly remarkable.

More precisely, Australia as a country has ratified the Paris agreement, aims for a weak greenhouse gas emissions reduction target of 26-28% by 2030 compared to 2005, and pursues an unimpressive goal of roughly 23% renewable energy (RE) electricity by 2020b (sufficient projects have now been approved to meet and exceed this goal).1 In this framework, beyond the dates aforementioned there are no further commitments, neither for greenhouse gas emissions reduction nor for RE electricity.

This is astonishing given the fact that the flora and fauna of Australia already severely suffer from the ongoing climate crisis characterized by weather disasters, including in the country; bushfires, droughts, and floods. These disasters are negatively impacting key sectors of the Australian economy, among which tourism and agriculture, notably.2 The position of the Federal Government is clearly influenced by the intense lobbying of the domestic heavyweight fossil fuel industry – in 2019, Australia was the World’s first coal exporter and second liquefied natural gas exporter (just behind Qatar) – is understandable, but deplorable considering what is at stake; nothing less than a sustainable future.3

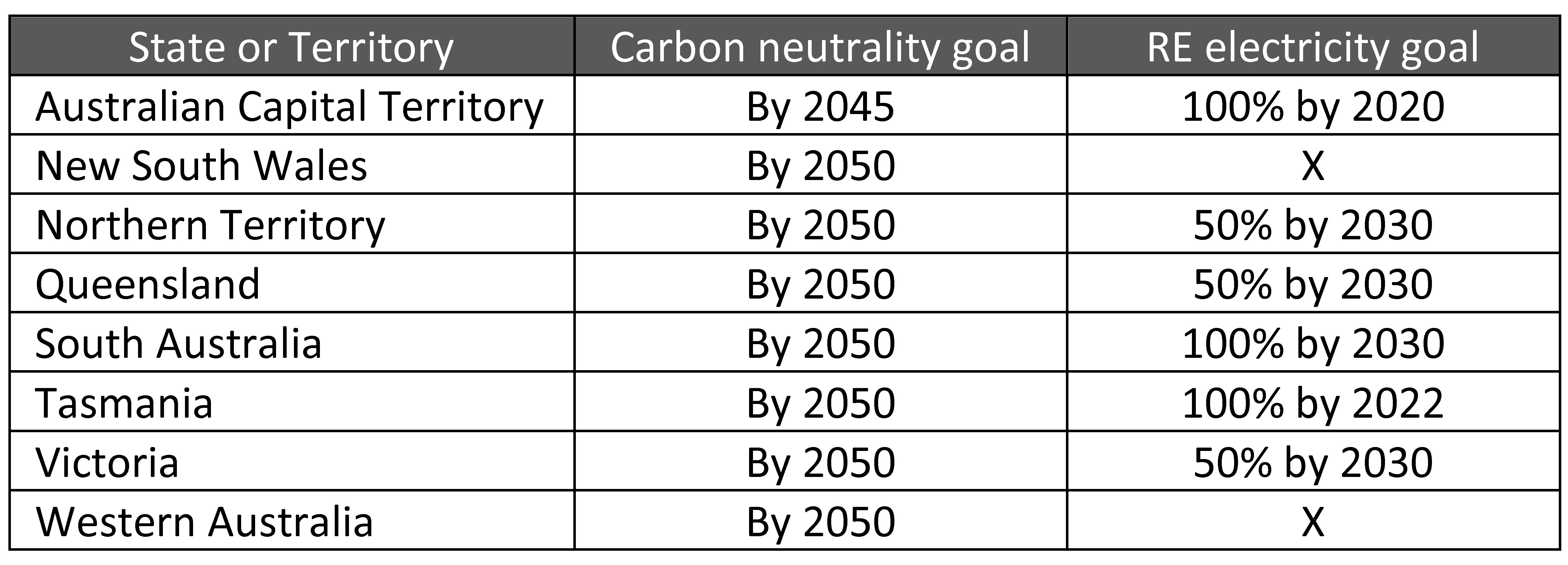

In comparison (Table), Australian States and Territories are less conservative and more forward-thinking to identify the economic, environmental, and social benefits of a clean growth. These political jurisdictions are stepping up to fill the void created by the Federal Government’s lack of credible climate and RE policies. They now all have adopted climate neutrality targets to be reached by 2045-2050. And the majority also have dynamic RE electricity goals in place; 50% or 100% to be realized in the period 2020-2030. These developments result in Australia having a de facto carbon neutrality target supported by high RE electricity goals.

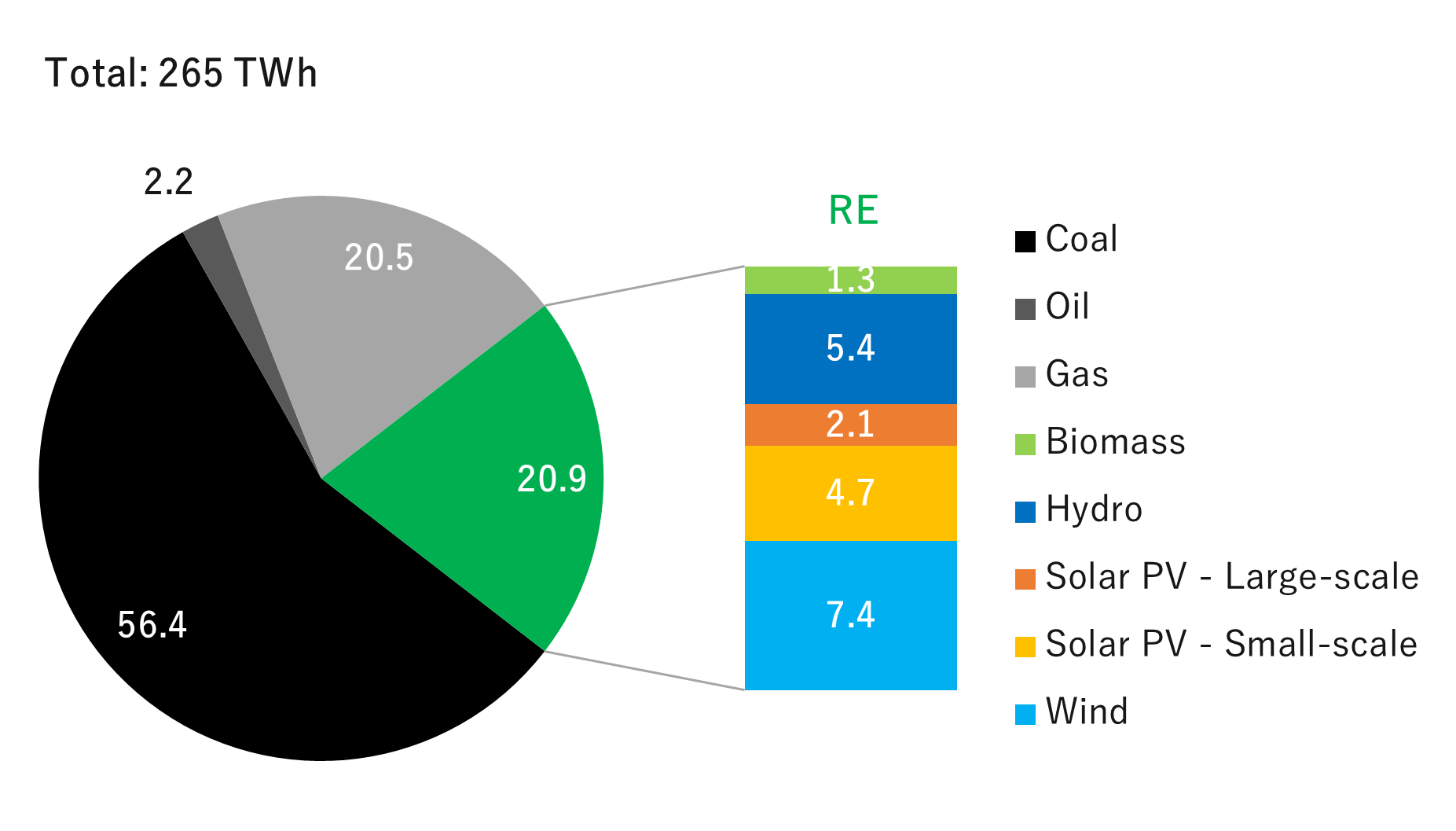

To turn these ambitions into realities and make Australia a RE powerhouse there is, however, a long way to go. Indeed, as of 2019, fossils – especially coal – still largely dominated Australia’s electricity mix, with a combined share for coal, oil, and gas of almost 80%, against only more than 20% for RE (Chart 1). Nevertheless, on a more positive note, it may be noted as well that the share of RE increased by 12 percentage points in the past decade, essentially to the detriment of coal, thanks to growths in wind and solar photovoltaic (PV).4

Three key factors will support the further expansion of RE in Australia and lead to a significant change of the national electricity mix in the years to come: (1) Favorable energy policy developments at the sub-national level as previously mentioned, (2) excellent natural conditions for electricity generation from onshore wind and solar PV including very large resource potentials and high capacity factors of about 29-46% and 15-22%, respectively, and (3) continued technological progress for these two technologies.5

Regarding the potential of solar PV in particular, it is estimated at almost 72,000 terawatt-hour (TWh) per year in eastern and southeastern Australia only (areas for which data on a TWh per year basis could be found).6 This is around 270 times Australia’s total annual electricity generation (265 TWh in 2019), and 2.7 times the World’s total annual electricity generation (just over 27,000 TWh in 2019).7 Beyond eastern and southeastern Australia, the rest of the country also has excellent solar PV resources (Map 1). Some areas, however, especially in the center of the country are protected areas and there is no electricity transmission lines there.

As a result, there is economic reason for optimism as well; already today onshore wind and solar PV are the country’s two cheapest options for new utility-scale electricity generation, approximately $45 per megawatt-hour (/MWh) in average for both technologies on a levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) basis. These levels of prices compare relatively favorably even with other existing amortized generating capacity having delivered wholesale electricity prices between about $35/MWh and $75/MWh in 2019 (Chart 2).

As a consequence, the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO), the country’s main market operator, projects that, unless the energy transition slows down – which seems unlikely, between 26 gigawatts (GW) and 50 GW of new utility-scale variable renewable energy (VRE, i.e. wind and solar) – much more than the total 16 GW of existing and soon to be operational utility-scale VRE – will replace 15 GW or 63% of Australia’s coal-fired generation by 2040.8 Under the most aggressive assumptions, the AEMO even forecasts that close to 95% of the electricity of Australia’s main wholesale electricity market, the National Electricity Market (NEM) – in eastern and southeastern Australia, could come from RE in 2040.9

In addition to utility-scale RE, distributed solar PV is also playing an important role in greening electricity generation in Australia. As a matter of fact, nearly 70% of the country’s solar PV electricity generation currently comes from small-scale solar PV. The success of distributed solar PV in Australia may be attributed to several factors among which socket parity, various support schemes (e.g. States’ feed-in-tariffs, rebates, and interest-free loans) simplicity of the installation administrative process, and high proportion of single-family homes.10 More specifically regarding socket parity, the LCOE for rooftop solar PV in Australia is about $65-100/MWh depending on locations (for a 7-kilowatt size system, typical for households). This LCOE compares with expensive residential retail electricity prices between $170/MWh and $295/MWh throughout the country. This means rooftop solar PV costs roughly only from just one-fourth to half of retail electricity prices.11

Thus, based on ambitious sub-national climate & energy policies and RE electricity cost advantage it is clear that RE is set to dramatically expand in Australia. Well-aware of the challenge of integrating high shares of wind and solar power, smart initiatives are now taking place in the country to make this change successfully happen in the coming years and decades.

Renewable Energy Integration

Three main solutions are advanced in Australia to massively deploy RE electricity: (1) Developing renewable energy zones (REZs), (2) increasing the penetration of batteries, and (3) establishing markets for green hydrogen.

Map 2: REZ Candidates in Eastern and Southeastern Australia

In June 2020, it was reported that Australia’s first REZ received a 27 GW deluge of applications for new energy generation, mainly wind and solar, and storage projects to connect to the 3 GW Central-West Orana REZ in New South Wales – a nine-fold oversubscription for clean power in the most coal power dependent State of the country (more than three-fourths of the State’s electricity in 2019). This striking result signals very strong interests from investors in competing to build large-scale RE projects which can benefit from economies of scale and of an efficient transmission system.12 An excellent start for this innovative approach in Australia, which should see construction of this first REZ begin in 2022.13

Picture: World’s Largest Lithium-ion Battery in the Hornsdale Power Reserve, Australia

South Australia has also been heavily investing in household battery storage, and it is now home to the country’s largest virtual power plant, coordinating 1,000 batteries combining for 5 MW. Into more details, the operation of a large number of solar and battery storage systems is controlled through software by an electricity retailer. This enables the generation, charge and discharge of the solar panels and batteries to be coordinated so that, together, the systems effectively operate as a power plant. In addition to these remarkable progress in South Australia, Tasmania which is hydro rich (more than 80% of the State’s electricity generation in 2019) aims to become the “Battery of the Nation.” Tasmania plans to achieve this vision by developing a new pumped hydro site (feasibility studies are conducted for three sites), and exporting the electricity generated to the State of Victoria via a new interconnector (the 1.5 GW high voltage direct current (HVDC) undersea Marinus Link which could be commercially viable in the 2030s or sooner).

Achieving Future Goals

Australia, a potential future superpower of a carbon neutral World, is awakening. It begins to recognize immense opportunities in a green growth based on RE, both to meet its domestic energy needs and as a source of incomes from exports.

One of the latest meaningful evidences confirming this change of paradigm is the Australia-ASEAN Power Link project by Sun Cable, a company headquartered in New South Wales. This project is a major energy infrastructure to supply RE electricity to the city of Darwin in the Northern Territory of Australia and Singapore. It will integrate three technology groups: (1) A 10 GW solar PV power plant, (2) a gigantic battery with an energy capacity of 30,000 MWh (over 230 times bigger than the battery of the Hornsdale Power Reserve), and (3) a more than 4,500 kilometers (km) HVDC transmission system from the solar/storage facility to the demand centers of Darwin and Singapore. More specifically, the transmission system is to be composed of an 800 km/3 GW overhead line from the solar/storage facility to Darwin, and of a 3,711 km/2.2 GW undersea cable from Darwin to Singapore (Map 3). The start of the project is planned for 2027.

To realize this future faster, however, national climate & energy policies should become more ambitious and also more transformative – which is currently the key hurdle or missing energy policy piece to completely unleash the substantial potential of RE in the country. Sub-national political jurisdictions have taken the leadership of the energy transition at different paces. Federal policies should back not slow down these efforts. In particular, Australia’s national Government may be inspired by Germany’s coal power phaseout by 2038, and the European Union’s policies for a just transition supporting workers and citizens of the regions most impacted by the energy transition. The fossil fuel industry has contributed to Australia’s wealth and may deserve some protection under the forms of compensations for planned closures for examples, but not by receiving unduly subsidies to continue operating in a deadlock, or by unnecessarily limiting RE expansion. Drawing a fair roadmap for the fossil fuel industry decline would definitely accelerate progress towards carbon neutrality.

The Australian domestic financial sphere is also sending messages in this direction after the country’s major banks recently aligned their positions towards thermal coal (used for electricity generation). Indeed, all of Australia’s big four banks have now set a date for exiting direct thermal coal investments: Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited, Commonwealth Bank of Australia, and Westpac Banking Corporation by 2030, and National Australia Bank by 2035.18

Last but not least, in Australia’s decarbonization enterprise is it highly unlikely to expect any contribution from nuclear power as the technology is banned by federal law in the country since 1998.19

Background Information20

In Australia, the Federal Government is in charge of the national energy policy. Sub-national Governments also have authority to advance their own energy strategies. This situation is somewhat similar to that of the United States.

There are two major electricity systems in the country with wholesale markets: The National Electricity Market (NEM) in eastern and southeastern Australia (Australian Capital Territory, New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, Tasmania, and Victoria) where over 80% of the country’s electricity is generated and consumed (regulated by the national Australian Energy Regulator). And the Wholesale Electricity Market (WEM) in western and southwestern Australia (Western Australia) where more than 15% of the country’s electricity is generated and consumed (regulated by the State’s Economic Regulation Authority). The independent Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) is in charge of system operations in these two markets. In northern Australia (Northern Territory) there is a minor isolated electricity system for the mining industry, which does not have a wholesale market. These three systems are not interconnected to each other.

In both the NEM and WEM, competition takes place in the generation and supply segments among State-owned (e.g. CS Energy, Synergy) and private (e.g. AGL Energy, Origin Energy, ENGIE) companies.

As for electrical networks, in the NEM, each political jurisdiction has a transmission company (e.g. Powerlink in Queensland, TransGrid in New South Wales, and AusNet Services in Victoria), and several distribution companies (e.g. Energy Queensland, also active as a supplier, Ausgrid). And in the WEM there is only one state-owned transmission and distribution company; Western Power.

- aAustralian States and Territories both are sub-national political jurisdictions with different organizations, i.e. the former have their own Governments and the latter are under the control of the Federal Government.

- bThe actual goal is for 33 terawatt-hours of additional renewable energy electricity compared to 1997.

- 1United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Australia First Nationally Determined Contribution (August 2015), and Australian Government, Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources, Renewable Energy Target Scheme – updated August 14, 2020 (accessed October 30, 2020).

- 2Climate Council, Icons at Risk: Climate Change Threatening Australian Tourism (February 2018), and Australian Government, Department of Agriculture, The Effects of Drought and Climate variability on Australian Farms (December 2019).

- 3BP, Statistical Review of World Energy 2020 (June 2020), and Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, Tim Buckley, Energy Transition Presents High Risks and Big Opportunities for Australia – February 6, 2020 (accessed October 2020).

- 4BP, op. cit. note 3.

- 5BloombergNEF, Levelized Cost of Electricity 1h 2020 (April 2020) (subscription required).

- 6Australian Energy Market Operator, 100 Per Cent Renewables Study – Modelling Outcomes (July 2013).

- 7BP, op. cit. note 3.

- 8Australian Energy Market Operator, Integrated System Plan 2020 (July 2020), and Generation Information (accessed October 30, 2020).

- 9Australian Energy Market Operator, 2020 ISP Generation Outlook (September 2020).

- 10Greentech Media, Jason Deign, What Other Countries Can Learn from Australia’s Roaring Rooftop Solar Market – August 3, 2020 (accessed October 30, 2020).

- 11Australian Energy Council, Solar Report (January 2020).

- 12PV Tech, Ben Willis, Australia’s First Renewable Energy Zone Receives 27 GW deluge of Applications – June 24, 2020 (accessed October 2020).

- 13New South Wales Government, Renewable Energy Zones (accessed November 5, 2020).

- 14Unless otherwise noted information from Climate Council, State of Play: Renewable Energy Leaders and Losers (November 2019).

- 15Hornsdale Power Reserve, Overview (accessed October 30, 2020).

- 16Unless otherwise noted information from Climate Council, op. cit. note 14.

- 17The Asian Renewable Energy Hub, Renewable Energy at Oil & Gas Scale (accessed October 30, 2020).

- 18Bloomberg, James Thornhill, Banks Don’t Want to Lend to Australia’s Coal Miners Any More – updated October 29, 2020 (accessed October 30, 2020).

- 19Australian Government, Federal Register of Legislation: Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Act 1998 (accessed November 5, 2020).

- 20International Energy Agency, Energy Policies of IEA Countries: Australia 2018 Review (February 2018).